Recently, I was asked to be a guest on KCUR 89.3, Kansas City’s NPR affiliate. I was joined by Audrey Navarro of Clemons Real Estate and Councilman Quinton Lucas of District 3.

The conversation was centered around how private developers, like Navarro, are investing in real estate development at a key intersection of the city that has been neglected for decades.

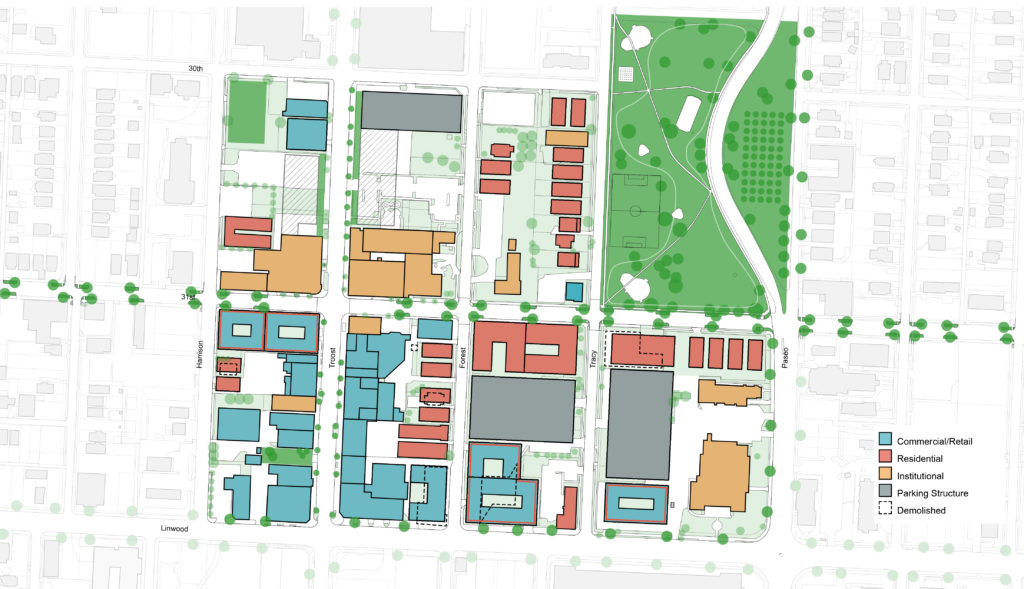

Today this area of 31st & Troost is attracting developers who see a future where vacant storefronts and lots are filled with new businesses and housing.

One vision includes millennials and entrepreneurs who opt for this stretch of the city since other former art and innovation districts are priced too high. Another vision, championed by the social service agencies and residents that have called this part of town their home for decades, imagines a neighborhood environment that directly benefits the predominantly low to moderate-income African-American residents who struggle to find opportunities for work and access to quality amenities and services.

I was in the studio as a representative of the KC-CUR initiative, which is leading a strategy for economic development on the east side that is inclusive and equitable. Steve Kraske, the host of KCUR’s Up to Date, quickly moved the conversation to the subject of gentrification. If you have a chance, listen to the segment HERE.

Otherwise, allow me to recap. First of all, gentrification is not ALL bad. Most people I survey will recognize the benefits of rising property values for residents and overall prosperity of a location.

The negative aspects most often discussed relate to the displacement of residents, and the inability of culturally similar populations to move to these ascending neighborhoods because they can not afford the prices.

That means that even if long-standing residents can stay, their desire to fill vacancies with friends and family who may share their socioeconomic status may not be attainable. In many cases, over time, these indigenous residents (usually most are renters) find themselves isolated, surrounded by other renters and property owners who now look more like white, college-educated professionals and empty-nesters.

So what can we do to avoid this? Addressing the implications of gentrification requires stakeholders to look beyond the data we can see today and consider the economic structures when the development vision is complete.

10 years from now, if trends continue and market forces not contained, what could this place look like?

We must imagine the full socio-economic profile in the future, ask ourselves if we are satisfied with that, and then backstep our way to today, where we have the opportunity to shape the future with the tools at our disposal. And what are those tools?

I am a strong proponent that we can overcome the negative implications of gentrification only with the three-legged stool of public, private and philanthropic partners.

The teeth lie with our policymakers who have the power to require affordability, incentivize inclusion, and leverage federal resources to fill financial gaps that occur when prices must be accessible to income-restricted renters and home buyers.

Philanthropy is also necessary to deploy their resources as thought-leaders and investors in the types of programs that build the capacity of non-profit organizations and induce collaborations that otherwise would not manifest.

Finally, the invisible hand of the private sector needs to cultivated and negotiated. There is no question that its power and money turns the dirt. But we must find ways to work with the market investors to develop the checks and balances that deliver the financial returns in harmony with the social and environmental benefits needed to revitalize a neighborhood and nurture its local wealth.

Written by me, Stephen Samuels, AICP